Solow's model (Solow-Swan model)

1. Basic Structure of the Solow Model

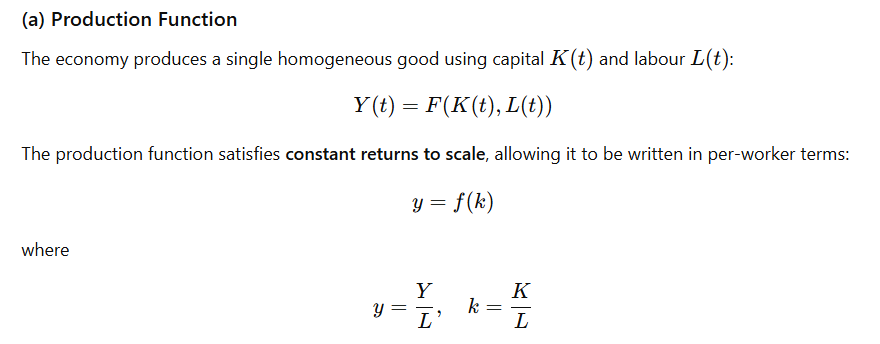

y → output per worker; k = capital per worker.

y → output per worker; k = capital per worker.

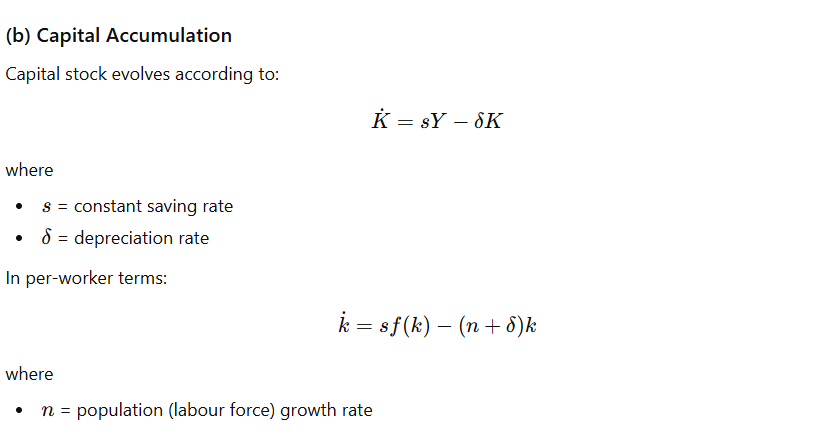

- sf(k) → investment per worker

- Saving creates new capital

- Raises capital per worker

- $delta k$ → depreciation per worker

- Machines wear out

- Reduces capital per worker

- $n k$ → capital dilution

- New workers arrive

- Same capital must be shared among more workers

- Even if total capital stays constant, capital per worker falls

2. Assumptions of the Solow Growth Model

The Solow model rests on several key assumptions, which define its structure and conclusions.

(1) Neoclassical Production Function

Constant returns to scale

Diminishing marginal product of capital

Positive but diminishing marginal productivity of inputs

This ensures convergence to a steady state.

(2) Single Good Economy

- One good is produced and can be used for both consumption and investment.

(3) Constant Saving Rate

Households save a fixed proportion of income.

Saving behaviour is exogenous, not derived from optimisation.

(4) Exogenous Population Growth

Labour force grows at constant rate nnn.

No migration or demographic transitions within the model.

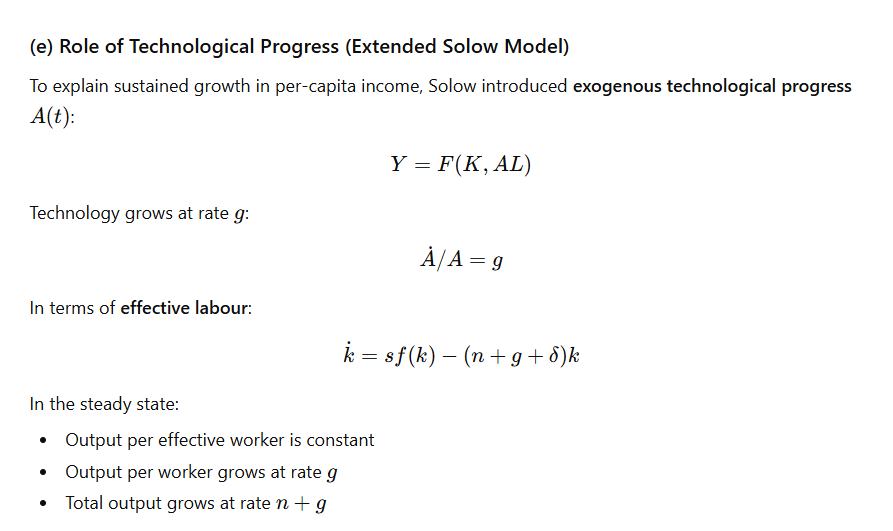

(5) Exogenous Technological Progress

Technology grows at a constant rate ggg.

The model does not explain the source of innovation.

(6) Capital Depreciation

- Capital depreciates at a constant rate δdeltaδ.

(7) Perfect Competition

Factors are paid their marginal products.

No monopoly power or distortions.

(8) Closed Economy

No international trade or capital flows.

Investment equals domestic saving.

(9) No Government Sector

No taxes, public expenditure, or fiscal policy.

Growth is driven purely by private saving and technology.

(10) Full Employment of Resources

All labour and capital are fully employed.

No involuntary unemployment.

3. Implications of the Solow Model’s Structure

Diminishing returns to capital imply that capital accumulation alone cannot sustain long-run growth.

Technological progress is the sole source of long-run per-capita growth.

Poor countries tend to grow faster than rich ones conditional on similar fundamentals (conditional convergence).

Policy variables (saving, population growth) affect levels of income, not long-run growth rates.

4. Significance of the Solow Model

Provides a benchmark framework for growth analysis

Explains cross-country income differences

Introduces the concept of steady-state growth

Forms the basis for modern growth theories, including endogenous growth models

Harrod’s model (Knife-edge model)

Harrod’s Model of Economic Growth

Harrod’s growth model (also called the Harrod-Domar model) is a dynamic Keynesian model that examines the conditions required for an economy to achieve steady growth. It emphasises the knife-edge instability of the growth process.

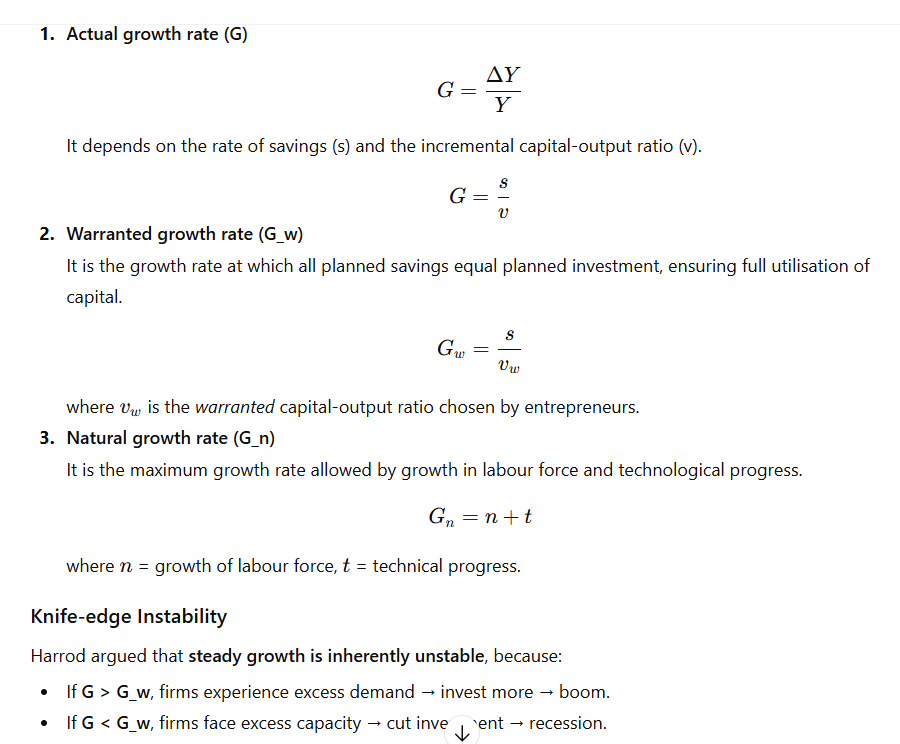

Harrod distinguishes among three types of growth rates:

Harrod’s Explanation of Trade Cycles

Harrod’s model implies that business cycles are inherent in the growth process of a capitalist economy. The interaction of the three growth rates generates fluctuations.

(a) Boom Phase

A boom begins when actual growth temporarily exceeds the warranted rate:

High profits raise expectations.

Induced investment increases.

Output and employment rise rapidly.

But the boom cannot continue indefinitely because the natural growth rate (Gn) imposes an upper limit.

(b) Downturn / Recession

Once actual growth falls below the warranted rate:

Firms face unutilized capacity.

They cut investment sharply.

Lower investment leads to reduced output and income.

Because investment is the driving force of growth, even a small drop creates a multiplier-accelerator contraction, producing a recession.

(c) Recovery

The slump persists until:

Undesirable inventory accumulation is corrected.

Capital stock shrinks relative to output needs.

New profitable opportunities emerge.

Then induced investment picks up again, starting a recovery.

Ramsey–Cass–Koopmans Model (RCK model)

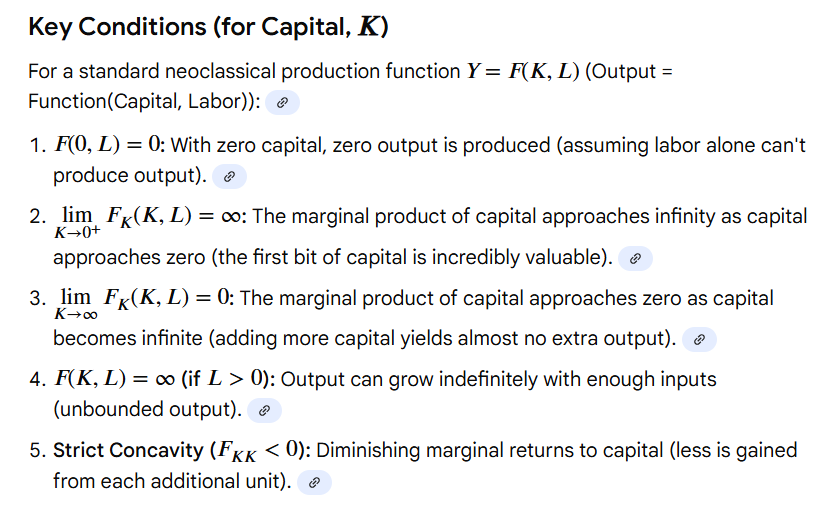

Inada conditions

Inada conditions are mathematical assumptions for production functions (like $Y=F(K,L)$) in economics, named after Ken-ichi Inada, ensuring smooth behavior and stable growth equilibria.

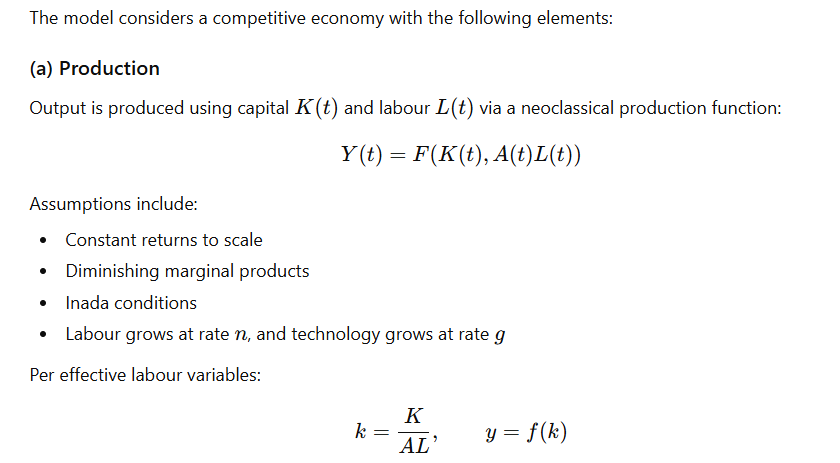

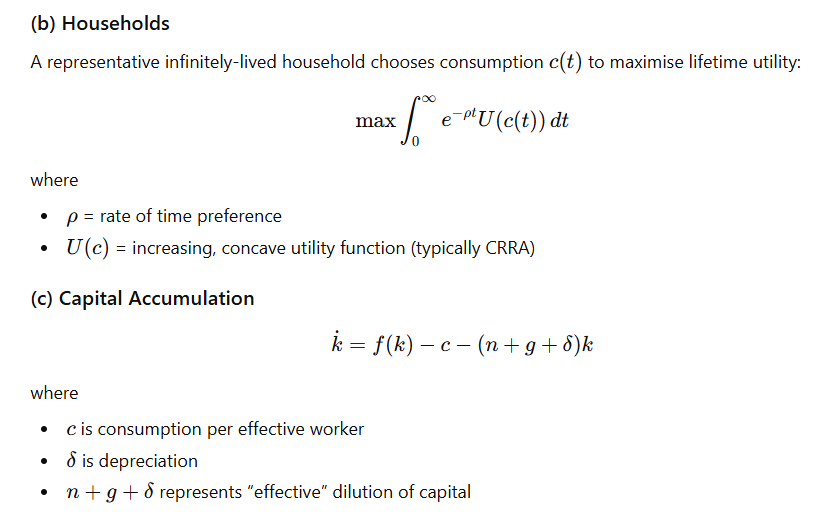

1. Basic Structure and Assumptions

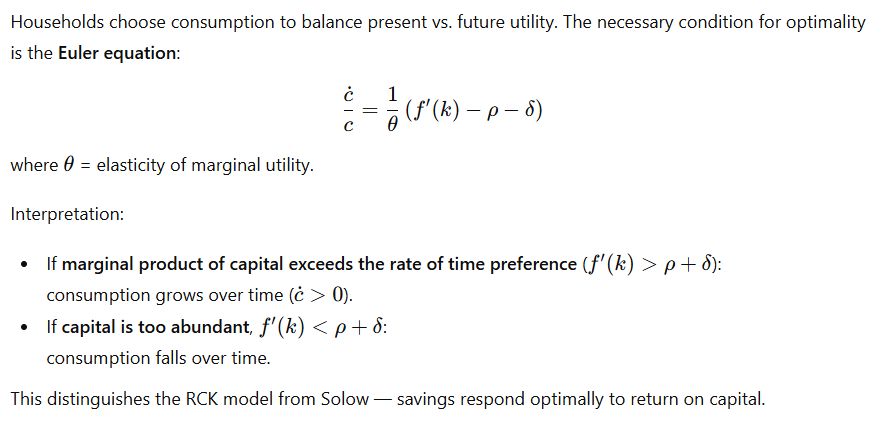

2. Optimal Consumption and the Euler Equation

(a) $ ho$ — Impatience / time preference

Measures how much we prefer today over tomorrow

Higher ρ hoρ = more impatient society

“I want enjoyment now, not later”

(b) $ heta$ — Aversion to inequality across time

Measures how uncomfortable we are with uneven consumption

Higher θ hetaθ = stronger desire to smooth consumption

“I hate big jumps in my standard of living”

(c) r — return on saving

If you save 1 unit today, it grows at rate rrr

More rrr → saving is more attractive

The Euler equation (now in symbols)

$$ rac{dot c}{c} = rac{1}{ heta}(r - ho)$$

This looks scary, but read it in words:

Consumption grows faster when the return on saving exceeds impatience.

Case 1: r>ρ

Saving pays well

Future consumption becomes attractive

Society postpones consumption

Consumption grows over time

Case 2: r<ρ

Society is very impatient

Future isn’t attractive enough

Consume more today

Consumption falls over time

Case 3: r=ρ

Perfect balance

Consumption stays constant

Role of $ heta$ (very intuitive)

θ hetaθ controls how fast consumption responds:

Large θ hetaθ → people strongly prefer smooth consumption

→ consumption changes slowlySmall θ hetaθ → people tolerate inequality

→ consumption changes rapidly

So θ hetaθ is like a shock absorber.

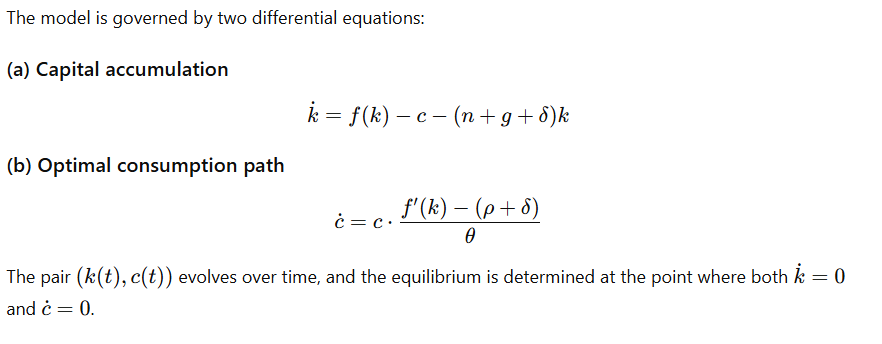

3. Dynamic System of the RCK Model

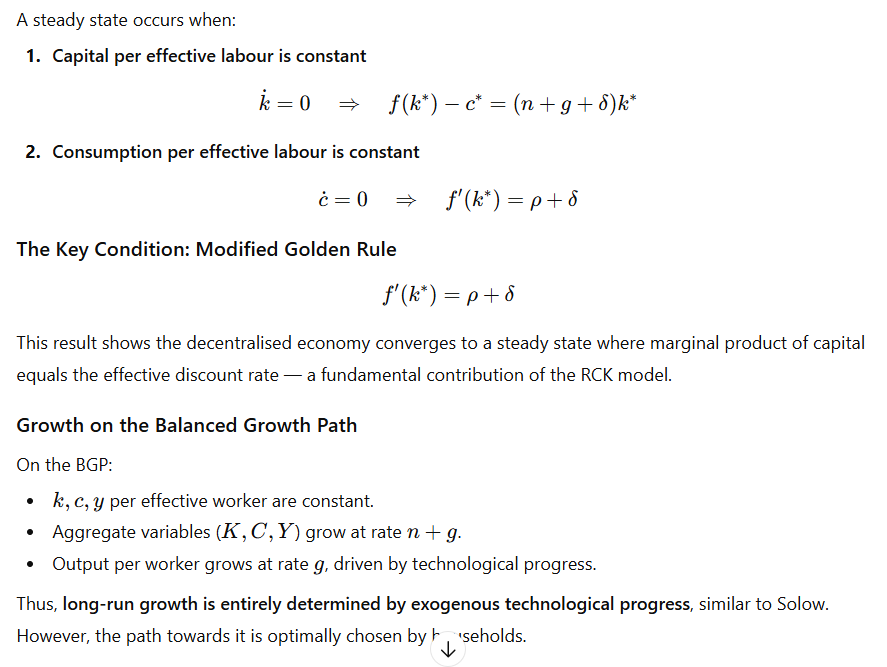

4. Steady-State and Balanced Growth Path (BGP)

5. Transitional Dynamics

A key strength of RCK is its saddle-path stability, meaning:

Only a unique path of (k,c)(k,c)(k,c) leads to the steady state.

Any deviation requires optimal changes in consumption to converge.

Graphically, the saddle path slopes upward, representing the optimal consumption choice given any level of capital.

This allows the model to explain how economies adjust when:

hit by shocks,

starting from different initial capital levels, or

experiencing changes in preferences or technology.

6. Comparison with the Solow Model

| Feature | Solow Model | Ramsey–Cass–Koopmans Model |

|---|---|---|

| Saving Rate | Exogenous | Endogenous (from optimisation) |

| Consumers | Passive | Utility-maximising |

| Dynamics | One equation (capital) | Two equations (capital + consumption) |

| Steady state | Determined by s | Determined by preferences + technology |

| Welfare analysis | Impossible | Possible |

The RCK model provides microfoundations for the saving rate and thus improves upon Solow.

7. Policy Implications

Interest Rate and Consumption

Higher returns on capital raise consumption growth.Taxation of Capital

Distorts optimality condition f′(k)=ρ+δ, potentially lowering welfare.Savings behaviour

Dependent on time preference: impatient societies save less.Transition policies

Governments can help economies move to the saddle path after shocks.

8. Significance of the RCK Model

Microfoundations for long-run growth

Endogenises savings and consumption decisions

Introduces intertemporal optimisation into macroeconomics

Explains transitional dynamics better than Solow

Forms basis for modern macro models (e.g., DSGE, endogenous growth theory)

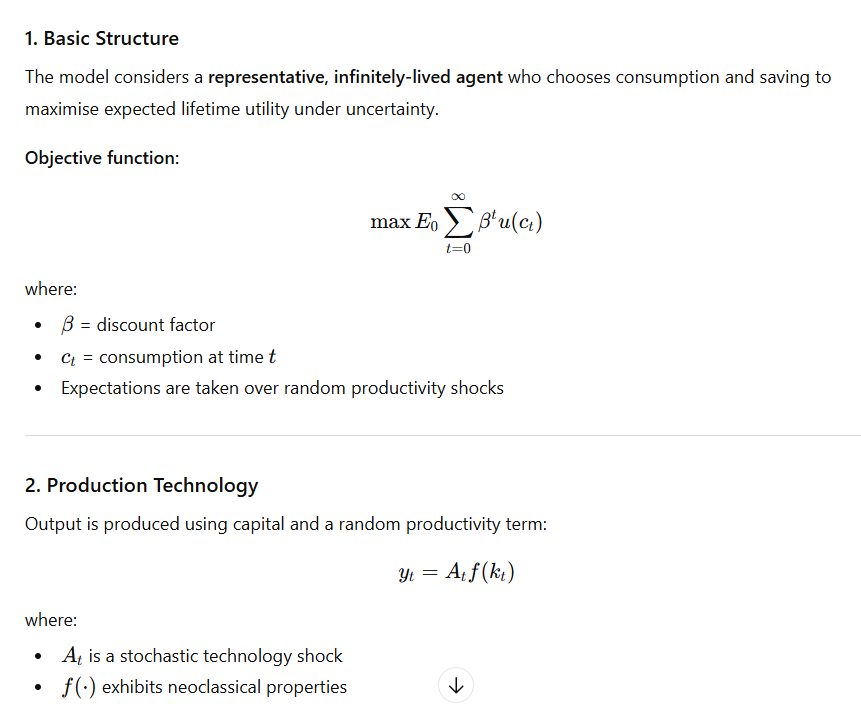

Brock-Mirman growth model

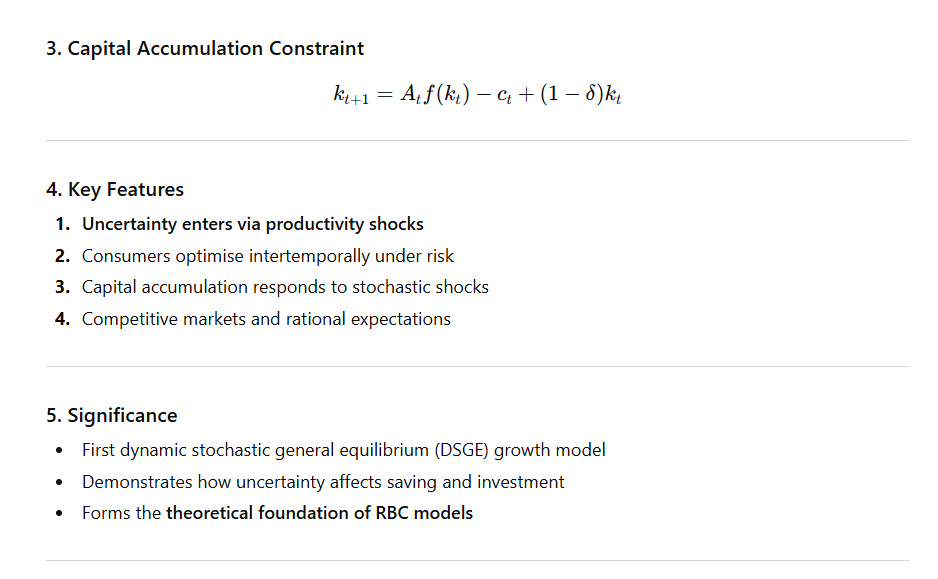

The Brock–Mirman model (1972) is one of the earliest stochastic optimal growth models and is considered a precursor to the Real Business Cycle (RBC) framework. It extends the Ramsey–Cass–Koopmans model by introducing uncertainty through stochastic productivity shocks.

Basic structure

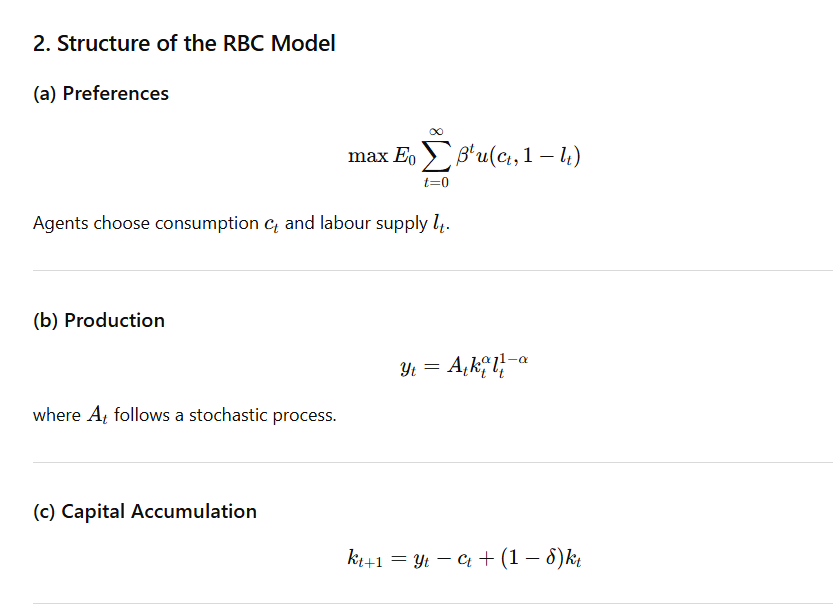

Real Business Cycle (RBC) Model

The Real Business Cycle model, developed by Kydland and Prescott (1982), explains economic fluctuations as optimal responses to real (technology) shocks in a perfectly competitive economy. Business cycles are viewed as efficient outcomes, not failures.

1. Core Assumptions of the RBC Model

Representative agent maximising lifetime utility

Perfect competition in goods and factor markets

Flexible prices and wages

Rational expectations

Technology shocks as the primary source of fluctuations

No role for monetary factors in explaining cycles

Structure

3. Mechanism of Business Cycles

Positive Technology Shock

Raises productivity

Increases output and wages

Households supply more labour

Investment rises

Economic expansion occurs

Negative Technology Shock

Lowers productivity

Reduces labour demand and output

Investment falls

Economy enters recession

Thus, business cycles arise from optimal responses to real shocks, not from market imperfections.

4. Key Results of RBC Models

Fluctuations are Pareto-efficient

No need for stabilization policy

Business cycles are equilibrium phenomena

Labour supply variation explains output volatility

Persistence arises through capital accumulation

5. Policy Implications

Countercyclical policies are unnecessary or harmful

Monetary policy has little real effect

Focus should be on productivity-enhancing reforms

6. Criticisms of RBC Models

Overemphasis on technology shocks

Cannot explain involuntary unemployment

Assumes unrealistic labour supply elasticity

Ignores nominal rigidities

Weak empirical evidence for large technology shocks

Kaldor’s model vs. Pasinetti’s model

Nicholas Kaldor and Luigi Pasinetti belong to the Cambridge (Keynesian–Neo-Ricardian) tradition of growth theory. While Pasinetti builds upon Kaldor’s framework, the two models differ significantly in their assumptions and conclusions regarding saving behaviour, income distribution, and growth.

| Basis of Comparison | Kaldor’s Model | Pasinetti’s Model |

|---|---|---|

| Basic Approach | Keynesian growth model linking growth with income distribution | Extension and correction of Kaldor’s model |

| Classes in Economy | Two classes: workers and capitalists | Same two classes |

| Saving Behaviour | Workers do not save; only capitalists save | Both workers and capitalists save |

| Saving Rates | Single saving rate out of profits | Different saving rates for workers and capitalists |

| Determinant of Growth | Growth determined by capitalists’ saving and investment | Growth independent of workers’ saving |

| Role of Income Distribution | Profit share adjusts to ensure equality of saving and investment | Profit share depends only on capitalists’ saving |

| Ownership of Capital | Capital owned only by capitalists | Workers can also own capital |

| Key Result | Higher profit share raises saving and growth | Workers’ saving does not affect long-run growth |

| Stability Condition | Requires profit share adjustment | More robust and theoretically consistent |

| Major Contribution | Links growth with functional income distribution | Resolves logical inconsistency in Kaldor’s model |

Explanation in Words (for Examiners)

Kaldor’s model assumes that workers consume all wages while capitalists save all profits. Growth depends on the profit share, which adjusts to generate the required saving for investment.

Pasinetti criticizes this assumption, arguing that workers also save and accumulate capital. Surprisingly, he proves that even when workers save, the long-run rate of growth and profit share are determined solely by capitalists’ saving behaviour.

This result is known as the Pasinetti Theorem, and it strengthens the logical foundations of the Cambridge growth models.

Endogenous growth theory

Endogenous Growth Theory explains long-run economic growth as the result of internal forces within the economy, rather than exogenous technological progress as assumed in the Solow model. It emerged in the 1980s, mainly through the works of Paul Romer and Robert Lucas, to explain sustained growth without diminishing returns.

A. Brief Account of Endogenous Growth Theory

2. Core Idea

The central proposition is that knowledge, human capital, innovation, and learning are produced within the economy through purposeful investment decisions. These factors generate increasing returns and positive externalities, enabling sustained per capita growth.

3. Role of Knowledge and Technology

Knowledge is treated as a non-rival and partially non-excludable good, meaning its use by one firm does not reduce availability to others. This leads to spillover effects that raise productivity across the economy.

4. AK Model

A simple representation is the AK model:

$$Y=AK $$ Here, A captures technology and institutional efficiency, while K includes both physical and human capital. Since marginal returns to capital do not diminish, continuous capital accumulation leads to sustained growth.

5. Romer’s Model (1986, 1990)

Romer emphasized research and development (R&D) and innovation. Firms invest in knowledge creation, which increases the stock of ideas. Knowledge spillovers ensure increasing returns at the aggregate level, sustaining growth.

6. Lucas Model (1988)

Lucas highlighted human capital accumulation through education and learning-by-doing. Individual investment in skills raises not only private productivity but also social productivity through externalities.

7. Role of Externalities

Endogenous growth relies heavily on positive externalities from education, innovation, and learning. These externalities offset diminishing returns to capital at the economy-wide level.

8. Policy Sensitivity

Unlike exogenous models, long-run growth in endogenous theory is policy-dependent. Government policies affecting education, R&D, trade, and institutions can permanently influence growth rates.

B. Importance of Endogenous Growth Theory in the Present Scenario

9. Explaining Persistent Growth Differences

The theory explains why some countries grow faster than others due to differences in human capital, innovation capacity, and institutions, rather than only capital accumulation.

10. Relevance for Knowledge-Based Economies

In today’s economy, growth is driven by technology, digitalisation, AI, and innovation, aligning closely with endogenous growth mechanisms.

11. Role of Education and Skill Development

With rapid technological change, continuous skill upgradation and education are crucial for productivity and growth, as highlighted by Lucas’ human capital model.

12. Innovation and R&D-Led Growth

Global competition makes innovation and R&D investment essential. Endogenous theory justifies public support for research due to knowledge spillovers.

13. Policy Guidance for Developing Economies

For developing countries, the theory supports investment in education, health, infrastructure, and institutions rather than relying solely on capital accumulation.

14. Globalisation and Trade

Trade openness enhances technology diffusion and learning, reinforcing endogenous growth through larger markets and innovation incentives.

15. Addressing Middle-Income Trap

Endogenous growth provides insights into escaping the middle-income trap by shifting from factor-driven to innovation-driven growth.

16. Inclusive and Sustainable Growth

Human capital–led growth promotes inclusion by expanding employment opportunities and improving productivity across sectors.

17. Long-Term Growth and Sustainability

Since physical capital faces limits, sustained long-term growth in the modern era depends on continuous productivity improvements, as emphasised by endogenous growth theory.

Schumpeter’s theory of capitalist development through innovations.

1. Role of Innovation

For Schumpeter, innovation is the fundamental force driving economic development. It involves introducing:

New products

New methods of production

New sources of raw materials

New markets

New forms of organisation

These innovations break the existing circular flow and create new opportunities for profit.

2. The Entrepreneur as the Agent of Change

The key figure in Schumpeter’s model is the entrepreneur, who:

Introduces innovations

Takes risks

Secures credit to finance new production

Disrupts existing patterns of economic activity

The entrepreneur is not a routine manager but a creative destroyer who changes the economic system.

3. Role of Credit and Banks

Innovation requires financing. Schumpeter assigns a central role to the banking system:

Banks create purchasing power by issuing credit

This enables entrepreneurs to acquire resources and implement innovations

Credit expansion thus becomes the engine of capitalist development

Without credit, innovations would not materialize.

4. Creative Destruction

Schumpeter famously stated that capitalism progresses through “gales of creative destruction.”

This means:

New technologies and firms destroy old ones

Existing monopolies are displaced by innovative rivals

Economic structures evolve continuously

Creative destruction explains why capitalism is dynamic but also unstable.

5. Business Cycles and Innovation Waves

Schumpeter linked innovations to business cycles:

Innovations occur in clusters, not individually

A major innovation (e.g., railway, electricity, IT) triggers investment, expansion, and a boom

As the innovation diffuses, profit opportunities decline → slowdown

Eventually leads to recession until new innovations emerge

Thus, capitalist cycles are endogenous, not the result of external shocks.

6. Long-Run Capitalist Development

Schumpeter argued that long-run development is a cumulative process:

Innovations raise productivity

Productivity growth increases income and employment

New industries emerge while older ones decline

Capitalism evolves through successive technological revolutions

This makes development non-linear and transformational.

7. Criticisms

Overemphasis on entrepreneurial role – ignores institutional and social factors.

Cyclical theory too dependent on innovation clusters – empirical debate.

Does not explain why innovations originate at specific times or places.

Assumes easy credit creation and downplays financial constraints.

Despite these critiques, Schumpeter’s insights remain highly influential.

Harrod’s classification of technical change. How does it differ from Hicks’ classification

Technical change refers to improvements in production methods that raise output from given inputs. Harrod and Hicks provide two influential ways of classifying technical progress, based on how technology affects factor productivity, factor proportions, and output–capital ratio.

1. Harrod’s Classification of Technical Change

Harrod (1948) classified technical progress on the basis of its effect on the capital–output ratio (v) when the economy grows at a steady rate. His classification is linked to growth neutrality — whether technical change maintains warranted growth conditions.

Harrod identifies three types of technical change:

(a) Harrod-Neutral (Labour-augmenting) Technical Change

Also called labour-saving or Harrod-neutral progress.

It increases labour efficiency, leaving capital productivity unchanged.

Effective labour becomes L(1+λ)L(1 + lambda)L(1+λ).

The capital–output ratio remains constant, preserving steady growth.

This is the form of technical change compatible with Harrod’s “warranted growth.”

(b) Capital-saving Technical Change

Increases the productivity of capital relative to labour.

For a given output, less capital is needed.

The capital–output ratio falls.

Raises profitability and can accelerate growth.

(c) Capital-using (or Capital-intensive) Technical Change

Requires more capital per unit of output.

The capital–output ratio rises.

Can slow growth unless accompanied by higher saving or investment.

Key Point:

Harrod’s classification is based on how technical change affects the capital–output ratio, which is central to his growth dynamics.

2. Hicks’ Classification of Technical Change

Hicks (1932) classified technical progress based on its effect on factor proportions, especially the marginal products of labour and capital along an isoquant.

Hicks identifies three types:

(a) Hicks-neutral Technical Change

Increases the marginal products of both capital and labour in the same proportion.

Leaves the ratio of marginal products unchanged.

Isoquants shift inward symmetrically.

(b) Labour-saving Technical Change

Raises the marginal product of capital relative to labour.

Firms substitute capital for labour.

Isoquants tilt, indicating more capital-intensive techniques.

(c) Capital-saving Technical Change

Raises the marginal product of labour relative to capital.

Firms substitute labour for capital.

Key Point:

Hicks classifies technical change by its substitution effects between labour and capital on an isoquant.

3. Differences Between Harrod and Hicks

| Basis | Harrod’s Classification | Hicks’ Classification |

|---|---|---|

| Underlying Concept | Capital–output ratio (v) and growth neutrality | Isoquant analysis and factor substitution |

| Focus | Effect of technology on steady growth | Effect of technology on marginal products and factor proportions |

| Definition of Neutrality | Neutral if v remains constant (labour-augmenting) | Neutral if MPK/MPL ratio unchanged |

| Relevance | Long-run macro growth theory | Production theory and microeconomics |

| Types Identified | Harrod-neutral (labour-augmenting), capital-saving, capital-using | Hicks-neutral, labour-saving, capital-saving |

| Implication of Neutrality | Only labour-augmenting technical change maintains steady growth | Neutral progress does not bias factor usage |

| Economic Meaning | Compatibility with warranted growth path | Changes in technology that alter input substitutability |

Government Failure

Government failure refers to situations where government intervention intended to correct market failure leads instead to inefficient allocation of resources, welfare loss, or unintended harmful outcomes.

1. Concept of Government Failure

Government failure occurs when:

Public policies do not achieve their intended goals,

Policies lead to misallocation of resources,

Social welfare is reduced rather than improved,

Costs of intervention exceed the benefits.

It stems from limitations in information, incentives, administration, and political processes.

2. Causes of Government Failure

(a) Imperfect Information

Governments often lack the detailed information needed to design efficient policies.

Example: Incorrect minimum support prices → distorted production patterns.

(b) Bureaucratic Inefficiency

Bureaucracies may be slow, wasteful, or driven by procedural rules instead of efficiency.

(c) Political Incentives

Policies may cater to vote banks, interest groups, or political bargaining, not social welfare.

Example: Subsidies continued despite inefficiency.

(d) Regulatory Capture

Industries influence regulators to frame rules that favour them rather than consumers.

(e) Moral Hazard and Corruption

Government programmes may encourage rent-seeking or leakages (e.g., corruption in welfare schemes).

(f) High Administrative Costs

Monitoring, enforcement, and compliance costs may exceed the welfare gain.

(g) Time Lags

Delay between policy design and implementation reduces effectiveness (e.g., fiscal policy lags).

3. Examples of Government Failure

Inefficient public enterprises with persistent losses

Fertilizer, electricity, and fuel subsidies leading to fiscal stress

Price controls causing shortages or black markets

Poorly targeted welfare schemes

Excessive regulation reducing innovation (“license raj”)

These illustrate that even well-intended interventions may create distortions.

5. Key Differences Between Market Failure and Government Failure

| Aspect | Market Failure | Government Failure |

|---|---|---|

| Definition | Inefficiency arising from market forces | Inefficiency arising from government intervention |

| Cause | Externalities, public goods, monopoly, imperfect information | Bureaucratic inefficiency, political incentives, poor design, corruption |

| Source of Failure | Private decision-making | Public decision-making |

| Corrective Mechanism | Government intervention | Policy reform, decentralization, market-based tools |

| Outcome | Welfare loss, inefficient allocation | Waste, distortions, fiscal burden, unintended consequences |

Behavioural Development Economics

Behavioural Development Economics has emerged as an important field that integrates insights from psychology, behavioural economics, and experimental evidence into the study of development. It challenges the assumptions and policy prescriptions of Traditional Development Economics by highlighting how real human behaviour diverges from rational, utility-maximising models.

1. Traditional Development Economics: Key Features

Traditional Development Economics (1950s–1990s), influenced by neoclassical and structuralist approaches, is based on the following assumptions:

(a) Rationality

Individuals are assumed to be fully rational, forward-looking, and consistent in decision-making.

(b) Perfect Information or Well-understood Constraints

Agents are assumed to know prices, risks, and consequences.

(c) Stable Preferences

Preferences do not change with context or framing.

(d) Focus on Structural Constraints

Development outcomes are explained by:

market failures

institutional weaknesses

poverty traps

capital shortages

poor infrastructure

Policies emphasised investment, structural reforms, human capital, and market efficiency.

2. Behavioural Development Economics: Key Features

Behavioural Development Economics modifies traditional assumptions by recognising that real-world individuals—especially the poor—face psychological, cognitive, and social constraints.

(a) Bounded Rationality

People have limited capacity to process information. Decisions often rely on rules of thumb.

(b) Present Bias

Individuals disproportionately value immediate rewards over future ones, leading to:

under-saving

under-investment in health and education

procrastination

failure to adopt beneficial technologies

(c) Limited Self-Control

Difficulty in following long-term plans, even when intentions are strong.

(d) Imperfect Information and Misperceptions

People make mistakes, misjudge probabilities, or rely on misleading beliefs.

(e) Social Norms and Peer Effects

Behaviour is shaped by:

social networks

cultural norms

community expectations

(f) Emotional and Psychological Factors

Stress, scarcity, and cognitive load affect economic choices.

(g) Evidence from Field Experiments

Behavioural development economists rely heavily on:

randomised controlled trials (RCTs)

impact evaluations

micro-level data

3. How Behavioural Development Economics Differs from Traditional Development Economics

| Aspect | Traditional Development Economics | Behavioural Development Economics |

|---|---|---|

| Human Behaviour | Fully rational, optimising | Bounded rationality, biases, heuristics |

| Decision-making | Based on prices, incentives, constraints | Influenced by psychology, framing, defaults, norms |

| Sources of Underdevelopment | Market failures, capital shortages, institutions | Cognitive biases, scarcity mindset, lack of self-control |

| Policy Tools | Regulation, investment, subsidies, macro reforms | Nudges, reminders, commitment devices, behavioural incentives |

| Approach to Poverty | Poverty as a resource/income problem | Poverty as a cognitive and behavioural trap |

| Methodology | Theoretical models + macro data | RCTs, behavioural experiments, micro evidence |

| Focus | Structural change, capital accumulation | Individual behaviour, micro-level decision-making |

| Intervention Design | Assumes agents respond predictably to incentives | Designs account for psychological reactions and biases |

4. Examples of Behavioural vs. Traditional Approaches

Savings

Traditional: Increase interest rates, improve banking access.

Behavioural: Automatic savings enrolment, reminders, commitment devices.

Health

Traditional: Build hospitals, reduce prices.

Behavioural: Use default vaccination appointments, small incentives, SMS reminders.

Education

Traditional: Increase school funding.

Behavioural: Provide information nudges, role models, motivational interventions.

Technology Adoption

Traditional: Subsidise new technologies.

Behavioural: Reduce complexity, demonstrate benefits through peer learning.

These examples show how small behavioural nudges can produce large improvements at low cost.

Concept of rights in a multi dimensional perspective

Rights are fundamental claims or entitlements that individuals possess by virtue of being members of society. Rights are multidimensional—that is, they encompass legal, political, social, economic, ethical, and developmental dimensions.

1. Legal Dimension

The legal dimension refers to rights guaranteed by the constitution, laws, and judicial systems. These include:

Fundamental rights (e.g., equality, freedom of speech)

Legal protections against discrimination or injustice

Enforcement mechanisms through courts

This dimension ensures that rights are codified, enforceable, and protected.

2. Political Dimension

Rights also involve active participation in civic and political processes. These include:

Right to vote

Right to contest elections

Freedom of association

Right to protest and express political opinions

Political rights empower individuals to influence governance and hold institutions accountable.

3. Economic Dimension

Economic rights concern access to resources and opportunities necessary for a dignified life:

Right to work

Right to minimum wages

Right to livelihood

Right to fair economic participation

These rights recognise that economic deprivation restricts individual freedoms, and development requires ensuring equitable economic opportunities.

4. Social Dimension

Social rights relate to living conditions and inclusion within society:

Right to education

Right to health

Right to social security

Right to non-discrimination (gender, caste, religion)

They highlight that human well-being is shaped by social structures, institutions, and collective norms.

5. Ethical and Moral Dimension

Rights are grounded in philosophical ideas of:

Human dignity

Justice

Equality

Respect for individual autonomy

This dimension asserts that rights are not merely legal claims but ethical imperatives reflecting universal moral values.

6. Cultural Dimension

Rights also involve recognition of cultural identity and diversity:

Right to language

Right to practise culture, tradition, and religion

Protection of indigenous and minority rights

This dimension emphasises that development must respect cultural plurality.

7. Developmental Dimension

Modern development thinking (UNDP, Amartya Sen) sees rights as central to expanding capabilities and freedoms. This includes:

Freedom from poverty

Freedom from exploitation

Access to opportunities that enhance human capabilities

Rights are thus viewed as both means and ends of development.

8. Interdependence and Multidimensional Nature of Rights

A multidimensional perspective stresses that rights are interdependent and mutually reinforcing:

Without education (social right), political participation is limited.

Without livelihood (economic right), freedom of speech has little meaning.

Without legal protection, all other rights become insecure.

Thus, rights must be approached holistically rather than in isolated categories.

Hysteresis & its consequences

Hysteresis refers to situations where temporary shocks or disturbances have permanent or long-lasting effects on the level of output, unemployment, or other macroeconomic variables.

Hysteresis in

- Unemployment

- Output and Growth

Consequences of Hysteresis

(a) Persistent Unemployment

Shocks during recessions raise unemployment for long periods, even after demand recovers.

(b) Permanent Loss of Skills and Human Capital

Long-term unemployment leads to declining productivity and employability.

(c) Lower Potential Output

Hysteresis implies that actual output affects potential output, contradicting traditional theory.

Economic downturns reduce investment, R&D, and productivity.

(d) Greater Role for Active Stabilisation Policies

Since shocks can have permanent effects:

Governments should use fiscal and monetary policy more aggressively,

Avoid deep and prolonged recessions.

(e) Breakdown of Natural-Rate Hypothesis

The idea that the economy naturally returns to full employment becomes invalid.

NAIRU (Non-Accelerating Inflation Rate of Unemployment) becomes history-dependent.

(f) Increased Inequality

Long spells of unemployment disproportionately affect vulnerable groups, widening wage and income gaps.

(g) Decline in Labour Force Participation

Discouraged workers permanently exit the labour market, reducing future growth.

(h) Structural Unemployment

Temporary shocks convert into structural changes in the labour market.

(i) Policy Errors Become More Costly

If hysteresis exists, inadequate stimulus during crises can lead to permanently lower economic performance.

Policy Implications

Strong countercyclical policies are needed to prevent hysteresis effects during downturns.

Investment in skills training, labour market programmes, and active employment policies is essential.

Preventing long-term unemployment is critical to preserving labour productivity.

Structural reforms must ensure flexibility but also safeguard workers from prolonged joblessness.

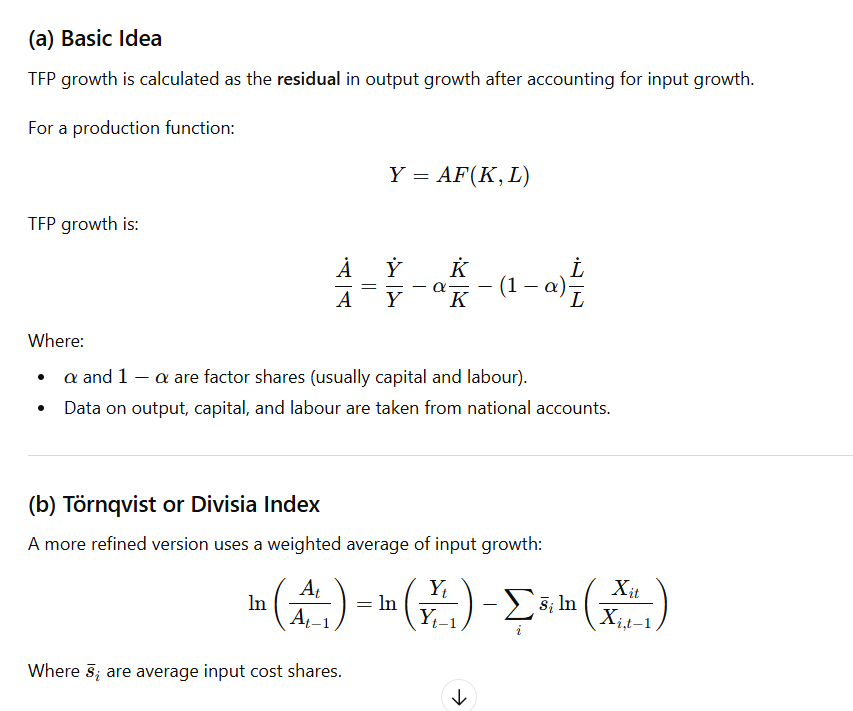

Index method and the Data Envelopment Analysis method

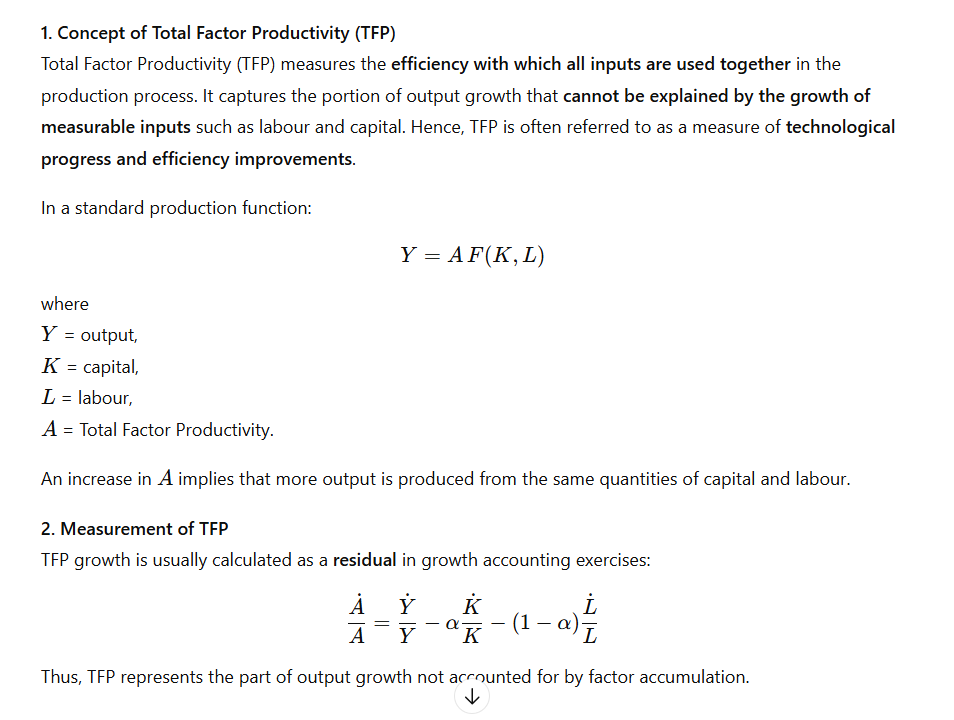

Total Factor Productivity (TFP) measures the part of output growth that cannot be explained by changes in inputs such as capital and labour. It captures improvements in technology, efficiency, skills, organisation, and innovation. Two widely used approaches to measure TFP are the Index Method and the Data Envelopment Analysis (DEA) Method.

Index Method

The Index Method is a parametric approach that measures TFP using index numbers based on observable changes in inputs and outputs over time.

Idea

(c) Advantages of the Index Method

Simple and easy to calculate using widely available macro data.

Useful for long time-series analysis (e.g., economic growth studies).

Based on national income accounting identity.

(d) Limitations

Requires accurate measurement of capital and labour, which is often difficult.

Assumes constant returns to scale and competitive factor markets.

Provides no separate measurement of technical change vs. efficiency change—TFP is a residual.

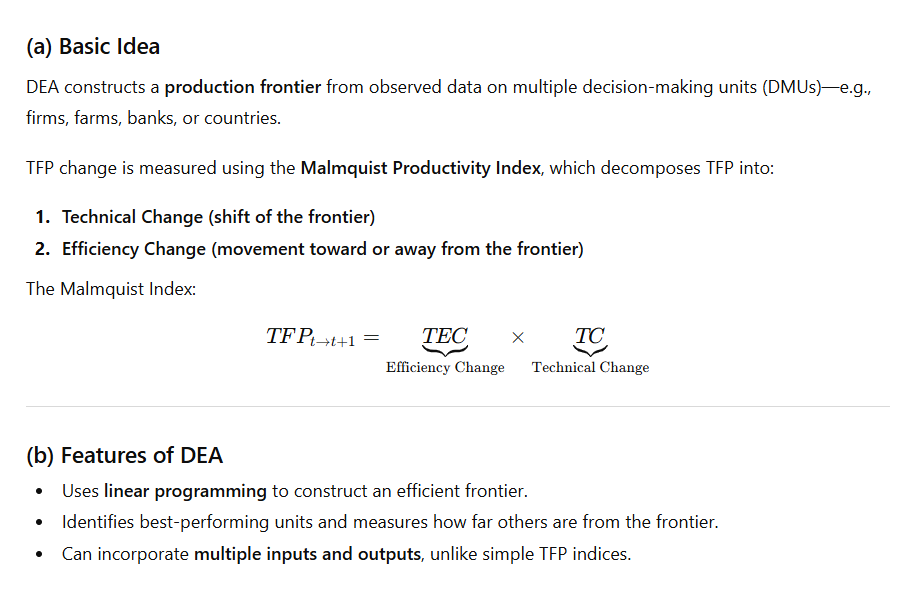

Data Envelopment Analysis (DEA) Method

DEA is a non-parametric, frontier-based approach used to measure TFP and efficiency when multiple inputs and outputs are involved.

It does not require a specific functional form of production and is data-driven.

Basic idea (technical change?)

(c) Advantages of DEA

No need to specify a production function (non-parametric).

Separates technical change from efficiency change—something the index method cannot do.

Works well with cross-sectional data and sectors with multiple outputs (e.g., banks, schools).

Useful when market prices for inputs/outputs are not available.

(d) Limitations of DEA

Sensitive to measurement errors and outliers.

Assumes all deviations from the frontier represent inefficiency.

Does not account for statistical noise.

Requires large datasets for reliability.

Key Differences Between Index Method and DEA

| Basis | Index Method | DEA Method |

|---|---|---|

| Type | Parametric | Non-parametric |

| Purpose | Measures aggregate TFP growth | Measures TFP + efficiency change |

| Data Requirement | Mainly macro time-series | Micro or sectoral cross-sectional data |

| Assumptions | Production function, factor shares | No functional form needed |

| Multiple Outputs | Difficult | Easily handled |

| Noise Handling | Economic theory-based | Sensitive to noise and outliers |

Total Factor Productivity (TFP)

Concept

Factors affecting TFP

1. Technological Progress

Advancements in technology, innovation, research and development (R&D), and adoption of new production techniques significantly enhance productivity.

2. Human Capital and Skills

Education, training, health, and skill development improve workers’ efficiency, adaptability, and ability to use advanced technologies, thereby raising TFP.

3. Institutional Quality and Governance

Efficient institutions, secure property rights, rule of law, low corruption, and effective governance improve resource allocation and productivity.

4. Infrastructure Development

Quality infrastructure such as transport, power, communication, and digital networks reduces transaction costs and improves overall efficiency.

5. Economies of Scale and Learning-by-Doing

Expansion of production leads to cost reductions through experience, specialisation, and learning-by-doing, which positively affects TFP.

6. Trade Openness and Global Integration

Exposure to international markets promotes competition, technology transfer, and better management practices, thereby enhancing productivity.

7. Structural Change

Shifting resources from low-productivity sectors (such as traditional agriculture) to high-productivity sectors (industry and services) raises overall TFP.

8. Financial Development

Efficient financial markets facilitate better allocation of capital to productive uses, encourage innovation, and improve productivity.

9. Macroeconomic Stability

Low inflation, fiscal discipline, and stable economic policies reduce uncertainty and encourage long-term investment, supporting productivity growth.

Methods of Measuring Total Factor Productivity

1. Growth Accounting Method (Solow Residual)

Assumes a specific production function (usually Cobb–Douglas)

Measures TFP as the residual after accounting for input growth

Simple and widely used

Limitations:

Sensitive to measurement errors

Assumes perfect competition and constant returns to scale

2. Index Number Approach

Constructs output and input indices

TFP growth = growth of output index − growth of input index

Common indices:

Tornqvist index

Divisia index

Merit: Allows multiple inputs

Limitation: Requires detailed data

3. Data Envelopment Analysis (DEA)

Non-parametric method

Uses linear programming to construct an efficiency frontier

Measures relative efficiency across firms or countries

Merit: No functional form required

Limitation: Sensitive to outliers and noise

4. Stochastic Frontier Analysis (SFA)

Parametric approach

Separates inefficiency from random error

Estimates a production frontier statistically

Merit: Accounts for statistical noise

Limitation: Requires functional form assumption

5. Total Factor Productivity Indices over Time

Malmquist Productivity Index

Decomposes productivity change into:

Efficiency change

Technological change

Widely used in panel data analysis.

How do property rights and transaction costs work to create institutions that influence development?

Institutions—defined as the formal and informal rules that structure economic behaviour—play a central role in shaping development outcomes. Two fundamental concepts in the New Institutional Economics framework, property rights and transaction costs, explain how institutions emerge and why they matter for economic development.

1. Property Rights and Development

Property rights refer to the legally and socially recognised claims individuals or groups have over resources, assets, and returns from their use.

(a) Function of Property Rights

Effective property rights:

Provide security of ownership

Individuals are more willing to invest in land, capital, and businesses when their claims are protected.Create incentives for productive activity

Secure rights ensure people can enjoy the fruits of their labour.Enable exchange and contracting

Clearly defined rights make it easier to trade, mortgage, rent, or use assets as collateral.Support efficient resource allocation

Markets function efficiently only when rights are clear and enforceable.

(b) Impact on Development

Well-defined property rights increase investment, innovation, and entrepreneurship.

They reduce disputes and encourage long-term planning.

Weak property rights result in informality, rent-seeking, and underinvestment.

Land reform or titling programmes often improve credit access and productivity.

Thus, institutional development often begins with securing property rights.

2. Transaction Costs and Development

Transaction costs are the costs of making economic exchanges. They include:

information costs

negotiation and bargaining costs

monitoring and enforcement costs

legal and administrative expenses

High transaction costs make markets inefficient or unworkable.

(a) How Transaction Costs Influence Institutions

Institutions evolve to reduce transaction costs. For example:

Legal systems reduce enforcement costs.

Contracts and norms reduce information asymmetry.

Regulated markets reduce uncertainty in trading.

Financial institutions reduce costs of borrowing and lending.

(b) Impact on Development

Lower transaction costs promote specialisation, trade, and investment.

High transaction costs discourage formal market participation and cause informal arrangements.

Poor governance, corruption, and weak enforcement increase transaction costs, slowing development.

Hence, institutions emerge as mechanisms for making transactions cheaper and more reliable.

3. How Property Rights and Transaction Costs Together Create Institutions

Institutions develop when societies recognise the need to:

Define ownership (property rights)

Reduce the cost of exchange (transaction costs)

Examples:

(a) Courts and Legal Frameworks

Courts enforce contracts and protect rights.

They reduce transaction uncertainty and disputes.

(b) Financial Institutions

- Banks rely on property rights (collateral) and reduce transaction costs in credit markets.

(c) Market Regulations

- Licensing, registration, and standard-setting bodies evolve to reduce transaction-related risks.

(d) Cooperatives and Community Institutions

- Informal institutions arise where formal systems are weak to guarantee rights and lower costs.

(e) Governance and Bureaucratic Institutions

- Land registries, patent offices, and regulatory bodies exist to define, record, and enforce rights efficiently.

Thus, institutions emerge as solutions to economic frictions.

4. Consequences for Economic Development

Higher Efficiency

Secure rights + low transaction costs → efficient markets → higher productivity.More Investment

Investors are more willing to invest when rights are secure and costs of contracting are low.Innovation and Entrepreneurship

Intellectual property rights incentivise innovation.Reduced Corruption and Informality

Strong institutions lower rent-seeking and increase formal participation.Inclusive Growth

Clear rights over land, credit, and resources empower disadvantaged groups.Better Allocation of Resources

Markets allocate land, labour, and capital more efficiently with strong institutions.

Geography impacts development

Geography has long been recognised as a fundamental determinant of economic development. Classical economists, economic historians, and modern development theorists have all emphasised that.

1. Geography as a Starting Condition for Development

Geography provides the initial conditions under which economies begin their development trajectories. These conditions influence:

agricultural productivity

population density

settlement patterns

trade possibilities

institutional evolution

Historical development patterns reveal persistent effects of early geographic advantages or disadvantages.

2. Climate and Agricultural Productivity

Temperate vs. Tropical Regions

Historically, temperate regions experienced:

moderate rainfall

fertile soils

fewer crop diseases

These conditions supported stable agriculture and surplus generation, which enabled urbanisation and specialisation.

In contrast, tropical regions faced:

soil nutrient depletion

pests and plant diseases

rainfall variability

This reduced agricultural surplus and constrained early capital accumulation.

Historical Evidence:

Europe’s agricultural surplus supported medieval towns and later industrialisation.

Many tropical economies remained agrarian with low productivity until modern technology.

3. Disease Environment and Human Capital

Geography strongly influenced disease burden.

Tropical regions had high prevalence of malaria, yellow fever, and sleeping sickness.

These diseases reduced life expectancy, labour productivity, and incentives to invest in education.

Historical Example:

European settlement was limited in high-mortality regions (e.g., Sub-Saharan Africa), affecting colonial strategies and institutional quality.

Acemoglu, Johnson, and Robinson show that disease environments shaped extractive vs. settler institutions.

Thus, disease geography had long-term effects on human capital formation and institutions.

4. Access to Waterways and Trade Routes

Geographic access to navigable rivers, coastlines, and natural harbours historically lowered transportation costs and facilitated trade.

Historical Examples:

River-based civilisations (Indus, Nile, Tigris-Euphrates) flourished due to irrigation and trade.

European coastal nations (Britain, Netherlands) benefited from maritime trade and colonial expansion.

Landlocked regions faced higher transport costs and limited market access.

Trade access allowed:

market expansion

technological diffusion

capital accumulation

These advantages persisted over centuries.

5. Natural Resources and Development

Geography determines resource endowments such as minerals, forests, and energy sources.

Positive Effects:

Coal deposits in Britain enabled the Industrial Revolution.

Oil resources transformed Middle Eastern economies.

Negative Effects (Resource Curse):

- Resource abundance sometimes led to rent-seeking, conflict, and weak institutions.

Thus, geography influences development through both productive and political channels.

6. Geography and Technological Diffusion

Geography affects how easily technologies spread.

Eurasia’s east-west axis allowed similar climates, easing diffusion of crops, animals, and technologies.

Africa and the Americas, with north-south axes, faced ecological barriers to diffusion.

This influenced the pace of agricultural and technological advancement across continents (Jared Diamond).

7. Geography and Institutional Development

Geographic conditions shaped colonial strategies and institutions.

In hospitable regions, Europeans settled and established inclusive institutions.

In disease-prone regions, colonisers set up extractive institutions.

These institutional differences persisted post-independence and continue to influence development.

8. Persistence and Path Dependence

Geographic effects exhibit path dependence:

Early geographic advantages enabled capital accumulation and institutional development.

These, in turn, reinforced growth through feedback mechanisms.

Thus, geography affects development indirectly and historically, rather than deterministically.

9. Limits of Geographic Determinism

Geography is not destiny.

Technological progress (irrigation, vaccines, air conditioning) reduces geographic constraints.

Policy choices, institutions, and human capital can overcome disadvantages.

Examples:

Singapore and Hong Kong prospered despite limited natural resources.

Green Revolution reduced climatic constraints on agriculture in India.

10. Interaction of Geography with Institutions and Policy

Modern development outcomes depend on the interaction of geography with:

institutions

technology

governance

global integration

Geography sets the stage, but institutions determine performance.

Role of the state in economic development

1. Theoretical Perspectives on the Role of the State

(a) Classical and Neoclassical View

The state should play a limited role, confined to:

law and order

property rights protection

national defence

Markets are assumed to be efficient, and state intervention distorts incentives.

(b) Keynesian and Structuralist View

Markets can fail due to unemployment, demand deficiency, and structural rigidities.

The state must actively intervene to:

stabilise the economy

promote investment

guide structural change

(c) Developmentalist State Perspective

Based on East Asian experience (Japan, South Korea, Taiwan).

The state plays a strategic and coordinating role in industrialisation and export promotion.

2. Correcting Market Failures

Markets often fail in developing economies due to:

externalities

public goods

information asymmetry

monopolies

State’s Role

Provision of public goods: infrastructure, roads, ports, power, law and order.

Regulation of monopolies and competition policy.

Intervention in education, health, and R&D due to positive externalities.

Without state intervention, private investment in these areas remains suboptimal.

3. Capital Formation and Infrastructure Development

Developing countries face shortages of capital and long gestation projects.

State’s Role

Mobilisation of savings through taxation and public borrowing.

Direct investment in:

infrastructure

heavy industries

basic manufacturing

Historical Evidence:

Public sector investment was central to industrialisation in India during the Five-Year Plans.

Infrastructure created by the state crowds in private investment.

4. Industrialisation and Structural Transformation

Economic development requires a shift from agriculture to industry and services.

State’s Role

Industrial policy to promote infant industries.

Protection, subsidies, and credit support during early stages.

Coordination of complementary investments (big push argument).

Examples:

East Asian economies used export-oriented industrial policies.

Strategic protection helped build global competitiveness.

5. Human Capital Formation

Markets underinvest in education and health due to long-term returns and externalities.

State’s Role

Public provision of education and healthcare.

Skill development and training programmes.

Nutrition, sanitation, and social infrastructure.

Human capital is essential for productivity growth and technological adoption.

6. Poverty Reduction and Social Welfare

Growth alone does not ensure equitable development.

State’s Role

Social security schemes.

Poverty alleviation programmes.

Employment generation (e.g., public works).

Redistribution through progressive taxation.

The state ensures that development is inclusive and socially sustainable.

7. Macroeconomic Stabilisation

Developing economies are prone to instability.

State’s Role

Fiscal policy to stabilise output and employment.

Counter-cyclical spending during recessions.

Management of inflation and public debt.

Stability is a prerequisite for long-term growth.

8. Institution Building and Governance

Institutions do not emerge automatically.

State’s Role

Establishment of legal systems and contract enforcement.

Protection of property rights.

Reduction of transaction costs.

Regulation of markets and financial systems.

Strong institutions improve investment climate and efficiency.

9. Global Integration and Development

Developing countries face asymmetric global markets.

State’s Role

Managing trade liberalisation.

Negotiating international agreements.

Protecting vulnerable sectors during adjustment.

Promoting exports and technological upgrading.

The state mediates between domestic priorities and global pressures.

10. Limits and Risks of State Intervention

While the state is essential, excessive intervention can cause:

bureaucratic inefficiency

rent-seeking and corruption

misallocation of resources

fiscal stress

This leads to government failure, as seen in inefficient public enterprises and over-regulation.

Hence, the challenge is not “state vs market” but effective state and efficient markets.

11. Changing Role of the State

The role of the state evolves with development stages:

Early stage: active intervention, planning, infrastructure creation.

Middle stage: regulation, coordination, human capital investment.

Advanced stage: facilitation, innovation support, social protection.

Modern development emphasises a capability-enhancing state, not a controlling one.

Impact of Economic Development on the Emergence and Functioning of Democracy

1. Economic Development and the Emergence of Democracy

(a) Modernisation Hypothesis

According to the modernisation theory (Lipset), economic development promotes democracy by:

raising income levels,

increasing literacy and education,

expanding the middle class, and

reducing extreme poverty.

These changes create social conditions favourable to democratic values such as tolerance, participation, and accountability.

(b) Social Structural Changes

Development transforms class structures:

Growth of an urban, educated middle class increases demand for political representation.

Decline of feudal or traditional authority weakens authoritarian control.

Historically, democracies in Western Europe and North America emerged alongside industrialisation.

2. Economic Development and Democratic Functioning

(a) Strengthening Institutions

Economic development provides resources to build:

effective bureaucracies,

independent judiciary,

professional electoral systems.

Stronger institutions enhance democratic governance.

(b) Reduction of Distributional Conflict

Higher incomes reduce zero-sum conflicts over scarce resources, making democratic compromise easier.

(c) Expansion of Civil Society

Development encourages:

media freedom,

voluntary organisations,

interest groups.

These institutions improve citizen participation and oversight.

3. Economic Development and Political Participation

Education increases political awareness and participation.

Economic security enables citizens to engage in politics beyond survival concerns.

Greater communication infrastructure improves information flow and accountability.

Thus, development deepens democratic participation.

4. Limits and Qualifications

Economic development does not guarantee democracy (e.g., authoritarian growth in some countries).

Democracies can emerge in poor societies but may be fragile.

Inequality can undermine democratic functioning even at higher income levels.

Historical, cultural, and institutional factors also matter.

Rural labour market institutions v/s Formal labour markets

1. Nature of Employment

Rural labour markets are dominated by casual, seasonal, and informal employment, mainly in agriculture and allied activities.

Formal labour markets offer regular, contractual employment with defined job roles and continuity.

2. Wage Determination

In rural labour markets, wages are often determined by:

local customs,

social relations (caste, gender),

implicit contracts, and

subsistence considerations.

In formal labour markets, wages are determined by:

productivity,

labour laws,

collective bargaining, and

market demand and supply.

3. Role of Social Institutions

Rural labour markets are embedded in social institutions such as caste, kinship, and patron–client relationships.

Formal labour markets are governed primarily by legal and contractual institutions, largely independent of social identity.

4. Contractual Arrangements

Rural employment often relies on oral, informal, and implicit contracts.

Formal labour markets rely on written contracts, legal enforcement, and standardised terms of employment.

5. Labour Mobility

Rural labour mobility is limited due to:

land ties,

social obligations,

lack of information, and

migration costs.

Formal labour markets allow higher mobility across firms and regions.

6. Job Security and Benefits

Rural workers face high job insecurity, with no social security or employment protection.

Formal workers enjoy benefits such as:

minimum wages,

pensions,

health insurance,

workplace safety regulations.

7. Role of Intermediaries

Rural labour markets often involve intermediaries (landlords, contractors, moneylenders).

Formal labour markets operate through transparent recruitment systems.

8. Information and Transparency

Information about jobs and wages in rural markets spreads through informal networks.

Formal markets rely on advertisements, employment exchanges, and digital platforms.

9. Power Relations

Rural labour markets often display asymmetric power relations, with employers exercising significant control.

Formal labour markets provide mechanisms for grievance redressal and worker representation.

10. State Regulation

State presence and enforcement of labour laws are weak in rural labour markets.

Formal labour markets are more effectively regulated and monitored.

Theory of path dependence

Path dependence is a concept in economics and social sciences which suggests that current outcomes are strongly influenced by historical events, initial conditions, and past choices, even when those choices were made under different circumstances.

1. Meaning of Path Dependence

Path dependence implies that:

History matters in economic outcomes.

Small, random, or temporary events can have long-lasting effects.

The economy does not always converge to a single efficient equilibrium.

Thus, the final outcome depends not only on fundamentals but also on the sequence of events.

2. Origins of the Concept

The idea was popularised by:

Paul David (1985) – study of the QWERTY keyboard.

Brian Arthur (1989) – increasing returns and self-reinforcing processes.

It is widely applied in development economics, institutional economics, and technology adoption.

3. Mechanisms of Path Dependence

(a) Increasing Returns

Early advantages lead to further gains, making one option dominant.

(b) Learning Effects

Users become more skilled with a particular technology over time.

(c) Coordination Effects

The value of a choice increases as more people adopt it.

(d) Adaptive Expectations

People choose options they expect others to choose.

(e) High Switching Costs

Changing to an alternative becomes costly once investments are made.

4. Path Dependence in Economic Development

(a) Institutions

Colonial institutions created long-term effects on governance and growth.

(b) Technology

Early adoption of certain technologies locks economies into specific trajectories.

(c) Industrial Location

Initial location of industries influences future clustering.

(d) Poverty Traps

Historical disadvantages can perpetuate underdevelopment.

5. Implications of Path Dependence

Multiple equilibria are possible.

History and timing matter.

Market outcomes may be inefficient.

Development is uneven across countries.

Policy interventions can alter development paths if timed well.

6. Criticisms

Overemphasis on history may underplay role of rational choice.

Difficult to empirically distinguish from persistence.

Some paths can be reversed with strong institutions and technology.

Increasing Returns, Monopolistic Competition, and Economic Growth

Traditional neoclassical growth models assume constant returns to scale and perfect competition, which imply diminishing returns to capital and limit long-run growth unless technological progress is exogenously given. Modern growth theory departs from this view by emphasising increasing returns to scale and monopolistic competition, which together provide a powerful explanation of endogenous and sustained economic growth.

1. Increasing Returns to Scale

Meaning

Increasing returns to scale occur when a proportional increase in inputs leads to a more than proportional increase in output. This is common in activities involving:

knowledge and ideas

research and development (R&D)

human capital

technology-intensive production

Knowledge is non-rival—its use by one firm does not reduce its availability to others—making increasing returns possible at the aggregate level.

Impact on Economic Growth

Sustained Growth

Increasing returns prevent diminishing returns to capital, allowing growth to continue without slowing down.Knowledge Spillovers

Innovations by one firm raise productivity of others, creating positive externalities that boost overall growth.Cumulative Causation

Early advantages reinforce themselves, leading to persistent growth and divergence across countries.Multiple Equilibria

Economies may settle on different growth paths depending on initial conditions.

Thus, increasing returns are central to endogenous growth.

2. Monopolistic Competition

Meaning

Monopolistic competition is characterised by:

many firms

product differentiation

some degree of monopoly power

free entry in the long run

This market structure is central to modern growth models such as those of Romer and Aghion–Howitt.

3. Role of Monopolistic Competition in Growth

Incentives for Innovation

Firms invest in R&D because temporary monopoly profits reward successful innovation.Product Variety Expansion

Growth occurs through an increase in the number of intermediate goods and product varieties, raising productivity.Endogenous Technological Change

Innovation results from profit-seeking behaviour rather than exogenous forces.Efficient Balance Between Competition and Monopoly

Monopolistic competition allows innovation while maintaining competitive pressure.

4. Interaction Between Increasing Returns and Monopolistic Competition

Increasing returns make perfect competition unsustainable, as firms must cover fixed R&D costs.

Monopolistic competition enables firms to recover these costs through mark-ups.

Together, they:

support continuous innovation,

generate self-sustaining growth, and

explain why growth can be persistent and uneven.

5. Limitations

Monopoly power may lead to inefficiency and inequality.

Excessive protection of intellectual property may reduce competition.

Early models predict scale effects that are not always observed empirically.

Economic Growth vs Economic Development

Meaning

Economic growth refers to a quantitative increase in a country’s output or income over time. It is usually measured in terms of increase in real national income, real GDP, or per capita income.

Economic development, on the other hand, is a broader and qualitative concept. It includes not only growth in income but also structural, institutional, social, and technological changes that improve the overall quality of life of the people.

Thus, economic growth is a necessary but not sufficient condition for economic development.

Distinction between Economic Growth and Economic Development

| Basis | Economic Growth | Economic Development |

|---|---|---|

| Nature | Quantitative | Qualitative and quantitative |

| Scope | Narrow concept | Broad and comprehensive concept |

| Focus | Increase in output/income | Improvement in living standards |

| Measurement | GDP, GNP, per capita income | HDI, poverty, literacy, health, inequality |

| Structural change | Not necessary | Essential |

| Income distribution | Ignored | Considered important |

| Time horizon | Short to medium term | Long-term process |

| Welfare aspect | Not explicitly included | Central objective |

Economic growth may occur without development, for example when income rises but poverty, inequality, unemployment, and poor health conditions persist, as seen in many developing countries.

Indicators of Economic Development

Economic development is multidimensional and cannot be measured by a single indicator. The important indicators are discussed below:

1. Per Capita Income

An increase in real per capita income indicates improved average material well-being. However, it is an incomplete indicator as it does not reflect income distribution or non-economic aspects of welfare.

2. Structural Change

Development involves a shift in:

Output and employment from agriculture to industry and services

Traditional techniques to modern technology

Informal sector to formal sector

Structural transformation is a key feature of sustained economic development.

3. Poverty Reduction

Decline in:

Headcount poverty ratio

Poverty gap

Multidimensional poverty

A reduction in absolute and relative poverty indicates that growth is inclusive.

4. Income Distribution and Inequality

Improvement in income distribution measured through:

Gini coefficient

Lorenz curve

Development requires that the benefits of growth are equitably shared.

5. Human Development Indicators

Introduced by UNDP, Human Development Index (HDI) includes:

Life expectancy (health)

Education (mean and expected years of schooling)

Per capita income (PPP)

HDI captures development beyond income.

6. Health Indicators

Life expectancy at birth

Infant Mortality Rate (IMR)

Maternal Mortality Rate (MMR)

Better health outcomes indicate improved quality of life and productivity.

7. Educational Indicators

Literacy rate

School enrolment ratios

Years of schooling

Education enhances human capital and long-term growth potential.

8. Employment and Quality of Employment

Reduction in unemployment and underemployment

Shift from casual to regular and productive employment

Development requires productive employment, not just job creation.

9. Social and Institutional Indicators

Access to basic services (water, sanitation, housing)

Gender equality

Social mobility

Quality of governance and institutions

Strong institutions support sustainable development.

10. Environmental Sustainability

Sustainable use of natural resources

Control of pollution and ecological degradation

Development must be environmentally sustainable, not growth at the cost of future generations.

Vicious Circle of Poverty

The vicious circle of poverty refers to a situation in which poverty perpetuates itself through mutually reinforcing economic and social factors, making it difficult for an economy or individuals to escape from low levels of income and development.

The concept was prominently discussed by Ragnar Nurkse, who argued that poverty is both a cause and a consequence of underdevelopment.

1. On the Supply Side (Low Productivity)

Low income →

Low savings →

Low investment →

Low capital formation →

Low productivity →

Low income

This cycle continues, trapping the economy at a low level of output.

2. On the Demand Side (Low Market Size)

Low income →

Low purchasing power →

Small market size →

Low inducement to invest →

Low productivity and output →

Low income

Thus, both supply and demand constraints reinforce poverty.

3. Human Capital Aspect

Low income →

Poor nutrition, health, and education →

Low labour efficiency →

Low productivity →

Low income

This creates intergenerational transmission of poverty.

Measures to break from it

1. Capital Formation and Investment

Increase domestic savings

Promote public investment in infrastructure

Encourage private and foreign investment

This raises productive capacity.

2. Big Push and Balanced Growth

Simultaneous investment in multiple sectors

Expansion of market size

Overcomes demand-side constraints

3. Human Capital Development

Investment in education, health, and skill development

Improved nutrition and sanitation

Enhances productivity and earning capacity.

4. Technological Progress

Adoption of modern technology

Productivity improvement in agriculture and industry

Raises output without proportionate increase in inputs.

5. Employment Generation

Labour-intensive industrialisation

Rural development and non-farm activities

Provides income and demand stimulus.

6. Institutional Reforms

Land reforms

Access to credit

Financial inclusion

Reduces structural inequality and exclusion.

7. Government Intervention

Public works programmes

Social security schemes

Targeted poverty alleviation programmes

Helps the poor escape subsistence-level income.

Demographic transition in developing economies

Demographic transition refers to the historical process through which a country moves from a regime of high birth rate and high death rate to one of low birth rate and low death rate, accompanied by changes in population growth and age structure.

Stage I: High Birth Rate and High Death Rate

Characteristic of traditional societies

Poor health facilities and low life expectancy

Population growth is slow

(Most developing countries have already passed this stage.)

Stage II: High Birth Rate and Declining Death Rate

Improvement in medical facilities and sanitation

Death rate declines rapidly

Birth rate remains high due to social and cultural factors

Leads to population explosion

Most developing economies experienced this stage during the early phases of development.

Stage III: Declining Birth Rate and Low Death Rate

Increased urbanization and education

Rising female literacy and employment

Use of contraception

Population growth rate begins to slow

Many developing countries, including India, are currently in this stage.

Stage IV: Low Birth Rate and Low Death Rate

Stable population

High level of development

Found mainly in developed economies

Characteristics of Demographic Transition in Developing Economies

Rapid population growth during Stage II

Declining mortality without a corresponding decline in fertility

High dependency ratio

Pressure on resources, employment, and social services

Potential for demographic dividend if properly managed

Importance of Population Policy in This Context

1. Controlling Population Growth

Population policy helps reduce fertility rates through:

Family planning programmes

Awareness campaigns

This prevents strain on economic resources.

2. Improving Human Capital

Policies promoting:

Education (especially female education)

Health and nutrition

Accelerate the fertility transition and raise productivity.

3. Realising Demographic Dividend

By:

Skill development

Employment generation

Population policy converts a large working-age population into an economic asset.

4. Reducing Dependency Burden

Lower fertility reduces the proportion of dependents, improving savings and investment capacity.

5. Promoting Gender Equality

Population policies encouraging:

Women’s empowerment

Delayed marriage

Have long-term demographic and economic benefits.

6. Sustainable Development

Population stabilization supports:

Environmental sustainability

Better access to housing, water, and health services

Export-led growth

Export-led growth (ELG) is a development strategy in which economic growth is driven by expansion of exports. The strategy emphasizes:

Production for foreign markets

Specialization based on comparative advantage

Integration with the global economy

According to this approach, exports act as an engine of growth by stimulating output, employment, productivity, and technological progress.

Mechanism of Export-Led Growth

Export-led growth promotes development through the following channels:

Increase in Aggregate Demand

Exports raise effective demand, leading to higher output and income.Foreign Exchange Earnings

Export earnings finance imports of capital goods, technology, and raw materials.Economies of Scale

Access to international markets allows firms to expand production and reduce costs.Technological Upgradation

Exposure to global competition encourages efficiency and innovation.Employment Generation

Export-oriented industries absorb labour, especially in manufacturing and services.

India’s Growth Strategy in the Context of External Trade

1. Pre-1991: Import Substitution Strategy

Before 1991, India followed an import-substitution industrialisation (ISI) strategy characterized by:

High tariffs and quantitative restrictions

Export pessimism

Focus on domestic markets

Exports grew slowly, foreign exchange shortages were frequent, and integration with the world economy remained limited.

2. Post-1991: Shift towards Export Orientation

After the New Economic Policy (1991), India gradually adopted elements of an export-led growth strategy:

Trade liberalisation

Reduction in tariffs

Removal of quantitative restrictions

Market-determined exchange rate

Promotion of export-oriented units (EOUs) and SEZs

India’s Current Strategy: Balanced Approach

Recent initiatives reflect a calibrated approach:

Make in India

Production-Linked Incentive (PLI) schemes

Export promotion coupled with domestic capacity building

India is moving towards a mixed strategy combining:

Export promotion

Domestic demand-led growth

Strategic protection where necessary

Consequences of climate change for the economy

Climate change refers to long-term changes in temperature, rainfall patterns, and the frequency of extreme weather events caused largely by human activities. Its economic consequences are wide-ranging and affect both developed and developing economies, particularly in the long run.

1. Impact on Agriculture and Food Security

Climate change adversely affects agricultural productivity through irregular rainfall, rising temperatures, droughts, floods, and soil degradation. Crop yields decline, production becomes more uncertain, and food prices rise, leading to food insecurity, especially in agrarian and developing economies.

2. Effects on Economic Growth